From forgotten wine cellars to silent olive mills, ancient structures reveal how climate change reshaped culture — and how heritage can guide a more resilient future.

When Walls Remember the Weather

Centuries before satellites tracked carbon or AI models forecast drought, humanity had its own climate sensors: stone, earth, and wood.

Every wall built for survival — a cellar, a mill, a granary — was designed in dialogue with nature.

These “food architectures” were not just factories of flavor; they were records of local climate adaptation, silent witnesses to environmental change.

Now, new research published in Heritage (MDPI) by Roberta Varriale and Roberta Ciaravino introduces a compelling concept:

“Food-related architecture as a climatic indicator” — a physical record of how past societies adapted to, and were transformed by, shifting environmental conditions.

(Varriale & Ciaravino, 2025, Heritage, 8, 423)

For Green Initiative, this research resonates deeply. It connects heritage, climate intelligence, and local economies, echoing our mission to empower destinations and organizations to become Climate Positive and Nature Positive through measurable action and cultural understanding.

Architecture as a Climate Indicator

The study proposes a revolutionary lens: when reliable meteorological data are absent, architecture itself becomes evidence.

A cellar designed to stay cool or a water mill abandoned after floods reflects not only economic cycles but also environmental transformation.

“The very existence of certain architecture designed to manage specific climatic factors is an indicator that, at the time of its construction, climatic conditions were compatible with them,” write the authors. “Similarly, their abandonment is a sign that those climatic conditions have changed.”

This transforms every mill and cellar into a data point — and every rural landscape into an open-air climate observatory.

Case Study 1 — Pietragalla: The Wine Cellars That Climbed the Mountain

In Basilicata, southern Italy, the small town of Pietragalla hosts over 200 rock-cut wine cellars, carved into sandstone hills. These “Palmenti” once formed the heart of local viticulture — cool, shaded, and close to vineyards.

MDPI Open Access

MDPI Open Access

But as temperatures rose, vineyards migrated uphill, seeking cooler altitudes. By the 1970s, the historic cellars were abandoned.

The architecture itself records the change: a literal climb of agriculture in search of equilibrium.

Today, Pietragalla’s wine district has been restored as an urban park within the Italian Environment Fund (FAI), but the lesson endures:

Climate change can rewrite landscapes faster than culture can adapt — unless adaptation becomes part of the heritage narrative itself.

Pietragalla’s story mirrors the challenges faced by mountain destinations in the Andes, Himalayas, or Costa Rica, where temperature shifts redefine both agriculture and tourism.

Case Study 2 — The Apulian Rock-Cut Olive Mills: Warmth, Work, and Abandonment

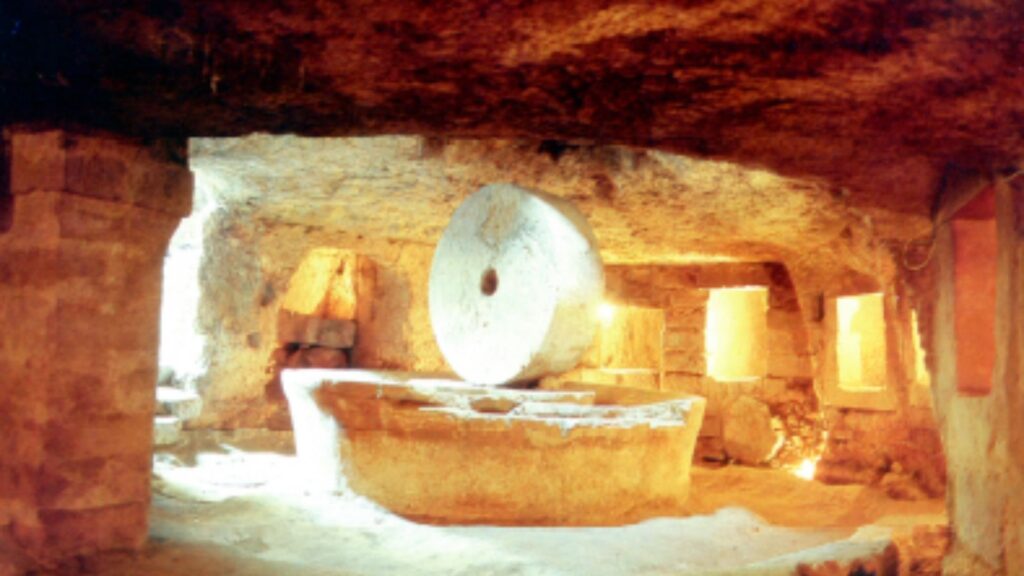

In the limestone lands of Apulia, more than 150 underground olive oil mills were carved beneath the soil between the 15th and 19th centuries.

They were engineering masterpieces: thermally insulated, self-heated by mules and workers, and optimized for pressing during the cold Little Ice Age (1590–1850).

MDPI Open Access

MDPI Open Access

As Europe warmed after 1870, production moved above ground.

The architecture of adaptation became the archaeology of change.

Today, these subterranean mills are both heritage sites and tourism assets, yet their climatic significance remains under-recognized.

Reframing them as climatic indicators could integrate them into wider climate education and regenerative tourism strategies — precisely what Green Initiative promotes through its Climate Positive Certification and storytelling frameworks.

Case Study 3 — Gragnano’s Valley of Mills: The Pasta District That Outlived Its River

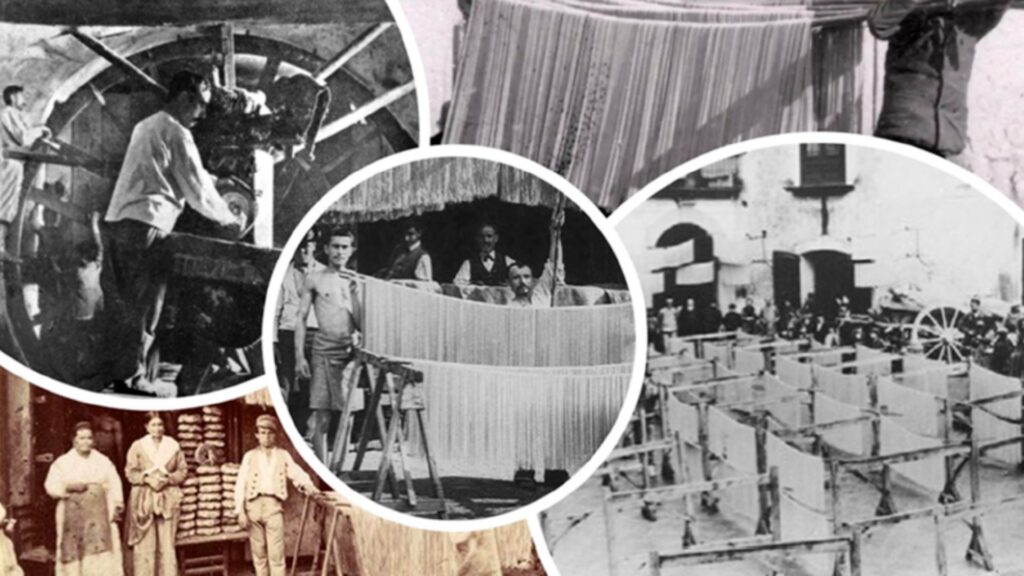

Near Naples, the Mills’s Valley of Gragnano became the heart of Italy’s pasta industry. The Vernotico River powered its mills and gave life to a thriving manufacturing district.

But shifting rainfall patterns turned prosperity into peril: catastrophic floods in 1764 and 1841 destroyed much of the infrastructure.

Over time, production transitioned to electric power, leaving behind silent towers and abandoned stone mills.

Today, Gragnano is a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) district, and the valley is listed by FAI and UNESCO. Yet, as rainfall extremes return, the past speaks clearly:

Hydrological instability is both a heritage story and a warning.

The parallels with Latin American river valleys are striking — from the Peruvian Andes to Brazil’s coastal basins — where water, culture, and resilience intersect.

Green Initiative integrates these lessons into climate adaptation planning, merging heritage protection with risk reduction and tourism decarbonization.

From Case Studies to Climate Intelligence

The Italian examples demonstrate that heritage can function as a living dataset, connecting cultural identity with long-term climate data.

By analyzing when and why structures were built or abandoned, researchers fill historical gaps in temperature and rainfall records — offering context for modern resilience strategies.

For Green Initiative, this aligns directly with our Climate & Nature Positive Framework, which helps destinations measure, monitor, and communicate environmental impacts holistically — encompassing emissions, biodiversity, and cultural adaptation capacity.

“These architectures remind us that every heritage site is also a climate lesson waiting to be learned.”

Linking Past Wisdom to Modern Action

| Heritage Insight | Green Initiative Response |

|---|---|

| Rural architectures reflect adaptation to environmental limits | Climate Positive Certification ensures measurable reductions and local ecosystem regeneration. |

| Abandonment reveals vulnerability to climate change | Nature Positive Programs strengthen ecosystem resilience and community awareness. |

| Architecture as storytelling of resilience | Sustainable Tourism Certification embeds heritage-based climate education. |

| Shared cultural identity as a driver of sustainability | Forest Friends Program connects communities through tangible restoration — reforesting memory as much as land. |

By connecting scientific evidence with practical frameworks, Green Initiative turns heritage into active climate governance.

From Italy to the World: Reading Climate in Stone and Soil

If Italy’s vineyards, olive mills, and rivers tell stories of adaptation, so too do Peru’s terraces, Costa Rica’s coffee estates, and Brazil’s coastal fisheries.

All are “food architectures” — designed ecosystems that mirror their climates.

Through projects in Machu Picchu, Cabo Blanco, and Bonito, Green Initiative extends this philosophy globally:

heritage is not only cultural — it is also climatic heritage.

Our certifications and partnerships ensure these landscapes continue to function as living climate indicators, guiding humanity toward measurable sustainability and community-based resilience.

Conclusion: From Abandonment to Regeneration

What Varriale and Ciaravino’s research reveals is that climate intelligence already exists in our past.

Abandoned cellars and mills do not mark the end of history — they mark the beginning of insight and responsibility.

“The introduction of the concept of climatic indicators aims to be an example of the potential of the humanities’ contribution to natural sciences,” the authors conclude, “also promoting the adoption of indirect sources when data are unavailable or unreliable.”

At Green Initiative, we share this conviction: heritage is data, and data is heritage.

By restoring, certifying, and communicating these connections, we turn loss into learning — and learning into leadership.

Reference

Varriale, R. & Ciaravino, R. (2025). Climate Change and Historical Food-Related Architecture Abandonment: Evidence from Italian Case Studies. Heritage, 8(10), 423.

MDPI Open Access

This article was written by Yves Hemelryck from the Green Initiative Team.